Hello and welcome back to another October here at the Third Row.

As I said last time, this month I’m diving into the surprisingly deep back catalog of the Hellraiser franchise.

This first step was, for me, a mix of old and new. The 1987 film is one I will admit up front to having a fondness for. At the same time, I confess to being a newcomer to Clive Barker's written works, finally reading The Books of Blood back in 2019. As a result, this marked my first time reading The Hellbound Heart, the original novel that Barker adapted the movie from.

Taking in both versions close to one another, to my pleasant surprise, served to enhance rather than detract. As the man behind both versions, Barker presents a largely faithful adaptation of his book. What changes he makes reflect the difference in mediums and benefits both.

I'm not putting these together just to play compare and contrast, however. In fact, the aspect I really wanted to focus on is one that plays the same in both versions. It’s also a topic that will be a major part of this month.

With that said, let's get into Pinhead, shall we?

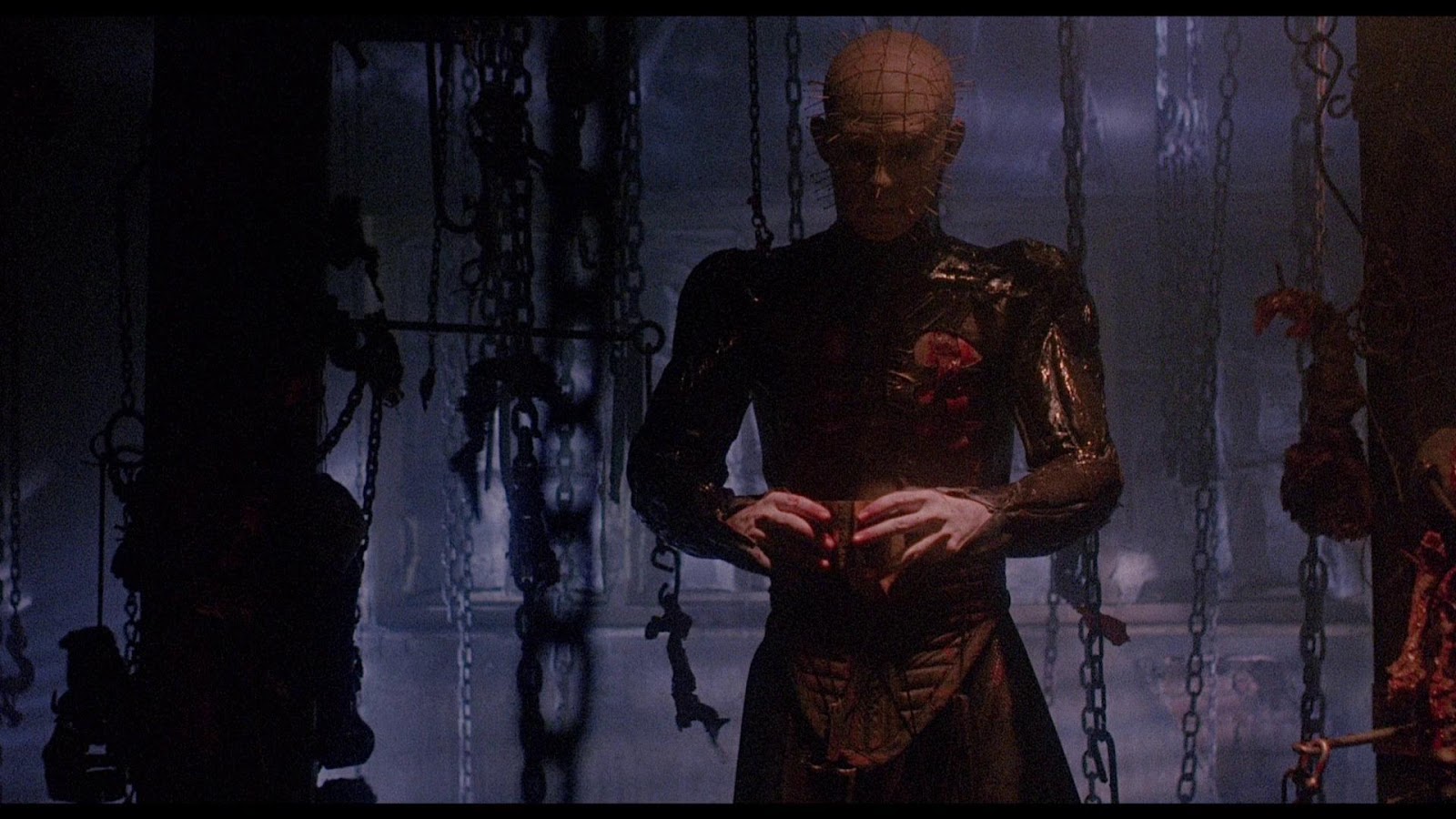

More than anything, to invoke the title Hellraiser calls to mind Douglas Bradley’s grid-faced priest of Hell. He is a horror icon on the level of Jason Voorhees, Michael Meyers, and Freddie Krueger.

Which makes it interesting that, in the beginning, this wasn't his story. In fact, the earliest form of the character is barely there.

If you were to have someone with no knowledge of the series read The Hellbound Heart in a vacuum and ask them where they would see a larger series coming from, they might correctly guess the Cenobites as a group, but still be hard-pressed to recognize the one member who would come to represent the series.

In fact, within the confines of the original novel, the character isn't even named as such (Pinhead was a behind the scenes nickname on the movie that fans adopted, becoming official in the sequels.) The Cenobite that matches the appearance is a supporting character who has maybe ten lines in the whole book, as a generous estimate.

Not a bad promotion, all things considered.

Of course, that’s for later entries, though they do factor into my thoughts here.

Hellraiser is one of those movies I remember liking as a teen for the shock value. The movie’s blood-soaked finale, in particular, where fugitive damned soul Frank Cotton is reclaimed by Hell in a display involving hooks and chains that is still an impressive, if graphic sight nowadays.

As an adult nearing 40, I still appreciate that. For one thing, it’s a great, grisly visual and kicks off the movie’s delightfully chaotic finale. Plus they have spent so much time setting up Frank as an utter bastard that it’s hard not to enjoy seeing him reap his karmic reward. With age, however, I’ve also come to appreciate just how the reduced rule of the Cenobites plays in the larger film, especially with regards to Frank’s aforementioned awfulness.

Contrary to the marketing, Pinhead and his cadre of torture priests aren’t the main villains of the movie. They aren’t summoned to do wrong or inflict torment on the innocent, they’re summoned in response to a misdeed. Instead, the core horror of the movie is focused on the dark, savage, and all too human love affair between Frank and Julia.

That human factor is part of what makes the story so interesting to me. Yes, for large parts of the film, Frank certainly doesn’t look the part (physically, he is a ghoul, made to feed on the blood of others in order to slowly restore himself) but his arc is still familiar, if amplified for horror. Frank is presented from the jump as a man in pursuit of pleasure - it’s his prime reason for seeking the puzzle box in the first place. He gets far more than he had bargained for, however, and instead spends most of the movie trying to find a way to cheat the consequences of what he agreed to. Julia is in similar straits - bored by her marriage to Frank’s brother, Larry, she has been harboring desires for the man she had an affair with years earlier. When Frank returns, however half-formed and appeals to her, she doesn’t have to be asked twice.

The decision to change Kirsty from just a friend to Larry's daughter.

It's an extra detail that adds to Frank's creepiness by giving his

leans into the delivery on "Come to Daddy.")

By comparison, the Cenobites are, despite their ethos of pain mixed with pleasure, strictly business - they come when the box summons them. They bring whoever summons them to Hell to be subjected to torments for all eternity. They are beings that could be described as horrifically principled. The only time we see them even slightly waver on their rules is a result of Kirsty accidentally summoning them, then bartering to avoid damnation. Even that flex is, ultimately, still within their jurisdiction - the box summons them and they can’t return empty handed. In order to give them someone in her place, Kirsty offers them a more tempting target - one who has broken their rules and that they would, otherwise, be unable to deal with unless he summoned them himself.

It goes back to an aspect of horror that I’ve resonated with more and more over the years - so many of the monsters mankind has dreamed are presented as beings with set rules. There are ways to deal with them, ways to avoid them, ways to summon them, and in some cases ways to defeat them. It’s not universal, of course, but often there is a sense of guidelines that are seen as irrefutable, or if refuted, the storyteller is called to task on.

As a result, they are often presented as more principled, reasonable, and, for lack of a better term, honor bound than human beings. Just as often as horror presents creatures with set rules of engagement, it presents stories about how the most disturbing aspects of human beings is how they will frequently skirt the bounds of what is acceptable or the social contract in pursuit of their own personal drives.

In this case, that means the beings who live and thrive in an alternate world where pain and pleasure are horrifically intertwined, despite a lifestyle built around sensation, are still framed to us as the creatures of (for lack of a better term) law and order, compared to the movie’s fugitive couple. Despite their menacing appearances and brutal means of dealing with those who are damned, they are ultimately seen as fair against the self-serving, ruthless counter of Frank and Julia, whose love is even secondary to self preservation.

While I don’t imagine marketing did it this way on purpose, the misdirect makes the movie into a great inversion of expectations that allows it to stand the test of time arguably far better than many of the movies that came after where our leather-bound sadomasochists take the center stage.

That, however, is a topic for later this month. For now, the time comes to put the box back on the shelf.

It won’t have long to gather dust, however. Keep an eye out, for soon we’ll be back here to discuss the fascinating, fantastical sequel that literally takes us to Hell in Hellbound: Hellraiser II.

Till then.

No comments:

Post a Comment